I’ve decided to start a series of video lessons teaching the application of Karnatic rhythmical techniques to Western music. This blog post is essentially a transcription of the video, for those that might prefer to read the material rather than watch it.

I’m going to be discussing some advanced rhythmical techniques that come from Karnatic music, which is the classical music of south India. Karnatic music is much more rhythmically complex than Western music, and part of that is they approach rhythm differently than we do in Western music. These techniques that I’ll be demonstrating have been developed Rafael Reina, who just released a book a couple weeks ago, Applying Karnatic Rhythmical Techniques to Western Music, published by Ashgate. I studied this material with Rafael at the Conservatory of Amsterdam for 7 years. The book covers a 5 year study program to really get in depth with all the material it covers, but I don’t want to talk about everything in it.

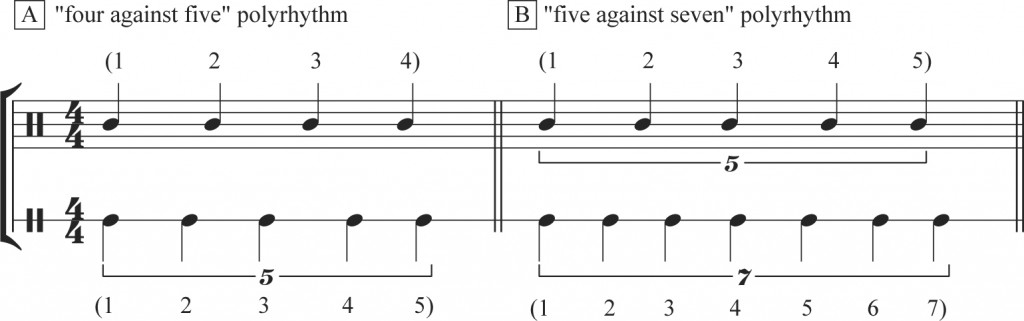

I want to discuss, over a series of lessons, some of the most practical elements that we can take from using these techniques, which help in complex rhythmical music that we see in Western music. These lessons will deal with things such as odd subdivisions of a beat like quintuplets and septuplets, odd meters like 5/8, 7/8, 11/8 or even more complex like 18/16, polyrhythms, polymeters, polypulses, tuplet ratios, embedded tuplets, and irrational rhythms like what we might see in the music of contemporary classical composers like Xenakis, Ligeti, Brian Ferneyhough, but also in modern jazz like Dave Holland, Steve Coleman, Weather Report, Vijay Ayer, in folk music from the Balkans and Africa, and also in electronic music from Aphex Twin, Squarepusher, Autechre, and Venetian Snares, and even in math metal from Tool, Meshuggah, Dillenger Escape Plan, and Coalesce. By really practicing and mastering this method, all of this music and rhythmical complexity that many people find very difficult and aren’t very comfortable with becomes much easier to understand and play after applying this karnatic approach to them. I’ll spend a few lessons explaining and demonstrating the fundamentals of this approach and then later I want to take it to a practical level and show how it can be used in rhythmically complex contemporary Western music by analyzing some pieces and explaining how to apply these Karnatic techniques to them to perform them correctly.

This first lesson is going to focus on subdivisions of a beat. Most Western music is based on a factor of 2 or 3, so eighth notes and sixteenth notes, or triplets. But Karnatic music regularly uses all the subdivisions, so including the odd ones 5, 7, and 9. So what I’ll demonstrate in this lesson is the Karnatic approach to beat subdivision.

GATIS

First I just need to discuss some of the vocabulary we’ll be using, because I’ll be using the Indian terms, which are different from Western music. It’s not essential that you memorize these in order to understand this method, but it will be helpful. I’ll also repeat them in context as we go through the lessons so you’ll become familiarized with them.

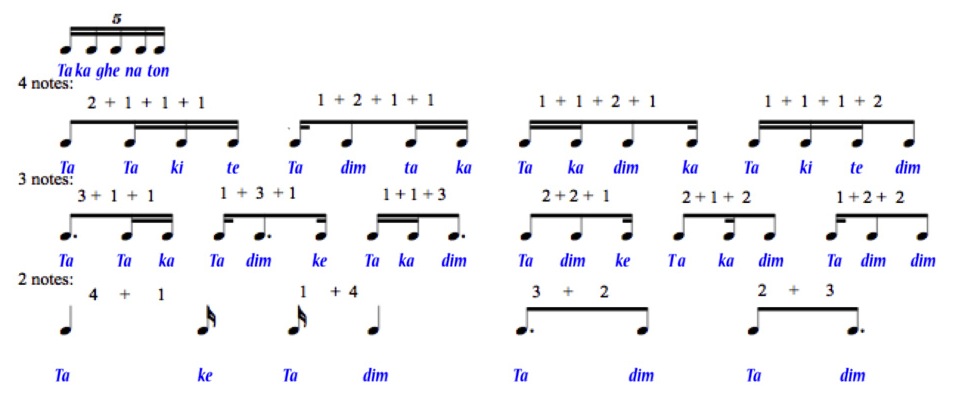

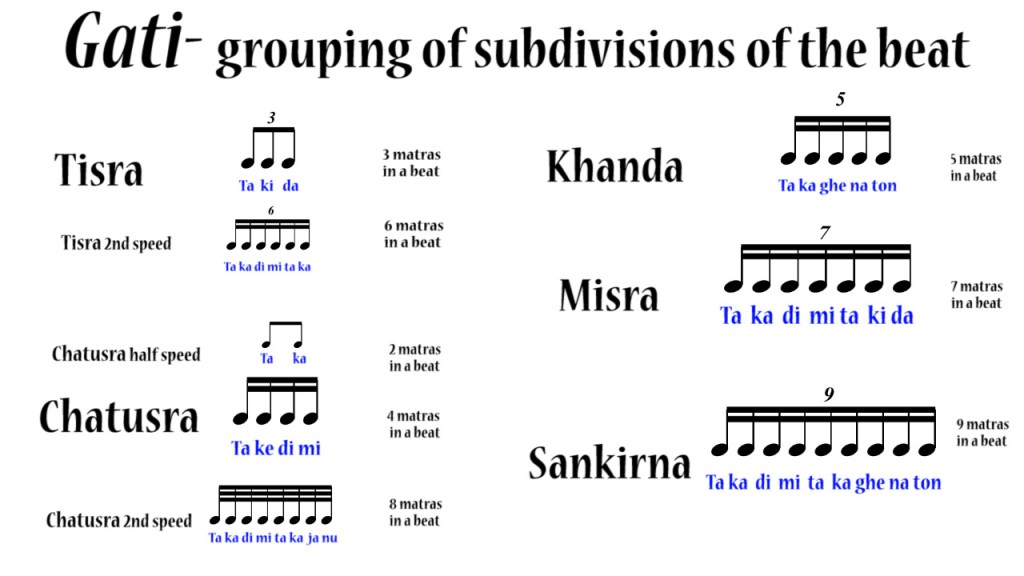

The first of these terms is Gati, and a gati is the name for a grouping of subdivisions of a beat. In a Western context, we call a three-note subdivision of a beat a triplet. In Karnatic music, this is called Tisra. Tisra is the name of the gati, so if I were to say this music uses the Tisra gati, it means it’s in triplets. The unit of subdivision of a gati is called a matra. So there are 3 matras in a triplet, or 3 matras in the gati Tisra, and it gets counted using the syllables Ta Ki Da. 4 matras in a beat, what Western music calls 16th notes, is the gati Chatusra, and it’s counted Ta Ka Di Mi. 5 matras in a beat, or quintuplets, is the gati Khanda and is counted Ta Ka Ghe Na Ton. 7 matras in a beat, or septuplets, is the gati Misra and can be counted in different ways, but for now we’ll use Ta Ka Di Mi Ta Ki Da. And the last gati is Sankirna, which is nonuplets or 9 matras, and can also be counted in different ways, but for now we’ll use Ta Ka Di Mi Ta Ka Ghe Na Ton. Sankirna is also a special case in Karnatic music, so I’m mentioning it now, but we won’t be using it consistently throughout these lessons.

Now you might be asking about some of the missing numbers like 6 and 8. Well, a sextuplet is twice as fast as a triplet, 3 x 2, so we call that Tisra second speed. Tisra is 3 matras and twice as fast, or times 2, is second speed. So 6 matras in a beat is Tisra second speed, and again this can be counted in different ways, but now we’ll use Ta Ka Di Mi Ta Ka. We have the same process for 8 matras, or 32nd notes. 32nd notes are twice as fast as 16th notes, so Chatusra 2nd speed, and we count that Ta Ka Di Mi Ta Ka Ja Nu. The last gati is 2 matras, or eighth notes, which is half the speed of Chatusra, so we’ll call it Chatusra half speed. Technically it has a different name in Karnatic music, but we’ll discuss that in later lessons.

SOLKATTU

So now I’ll demonstrate counting each of the gatis using these syllables, which is called Solkattu. What’s most important here is to really make sure that each matra is equally spaced within the gati. I’ll begin at a slow metronome marking so that when I get to the higher gatis it doesn’t become so fast that it’s uncontrolled and sloppy. I’ll do this now at 50, and I recommend that you practice these at a tempo between 40-60. Keep repeating the gati over and over until you’re sure that you’re keeping it consistent and every matra exactly in tempo.

Once you’ve mastered each gati on it’s own you should practice changing between them. Really focus on feeling the differences between neighboring gatis, especially on the higher end such as tisra 2nd speed and misra, and know what a subdivision of 6 vs a subdivision of 7 feels like. Start with switching back and forth between two gatis at first and slowly build it up to more. I’ll demonstrate a couple exercises now, but you can also write your own and even better, turn on a metronome and improvise switching between them, always making sure to keep each matra in each gati very precise and even.

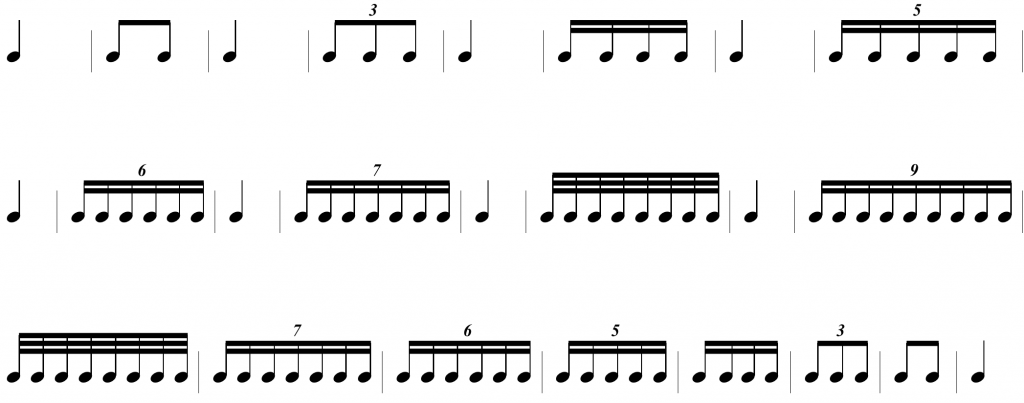

In this first exercise I’ll build them up with one beat in between, and bring them down all in succession. You could also do this exercise in reverse.

And then you can move on to irregular switching.

RHYTHMICAL PERMUTATIONS

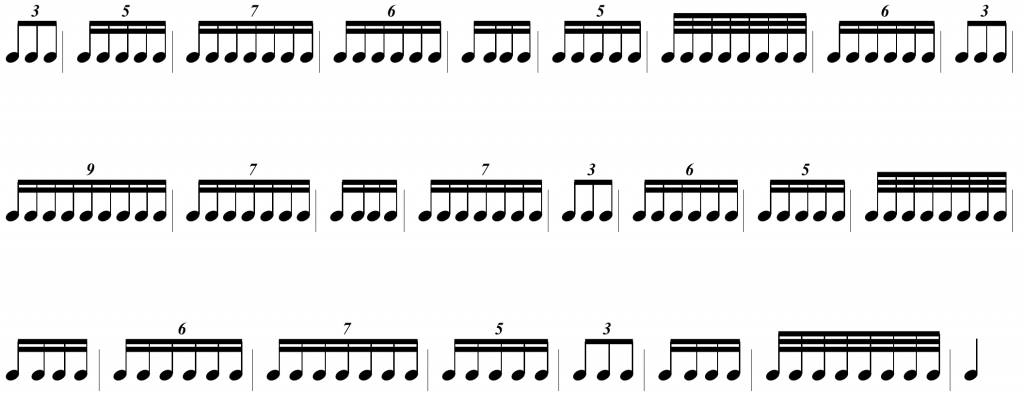

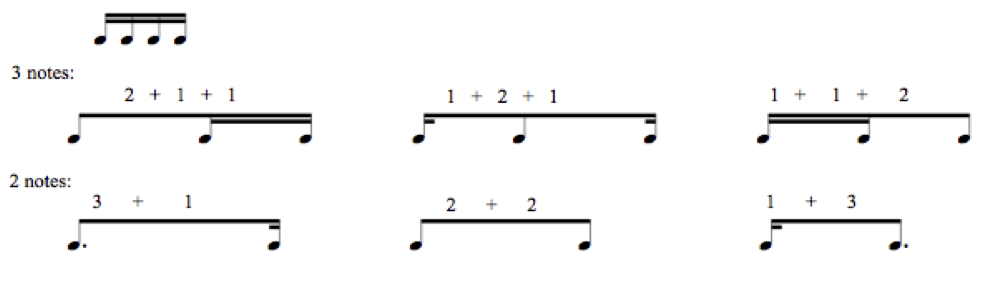

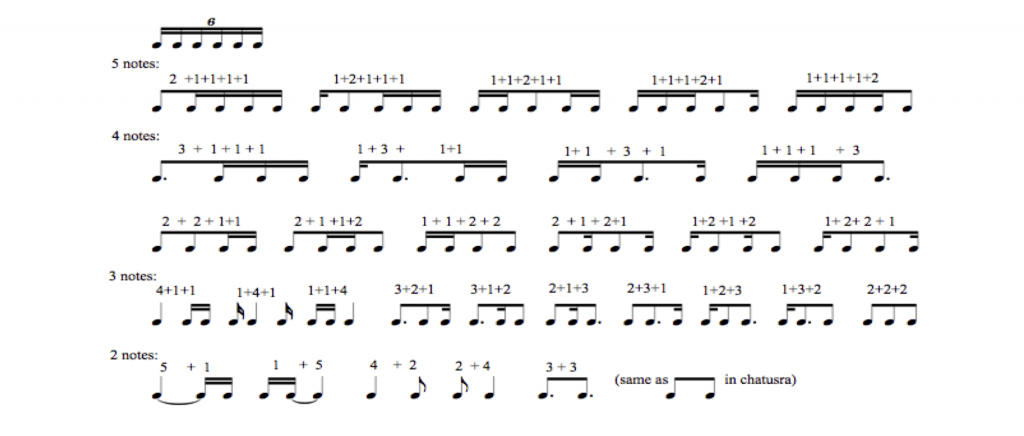

The next step is to practice using these gatis beyond just saying every matra, and introducing longer notes within each grouping. The first thing to do is to identify each possible permutation of each gati. We’re already familiar with tisra 1st speed and chatusra in Western music, so I’ll skip over those now.

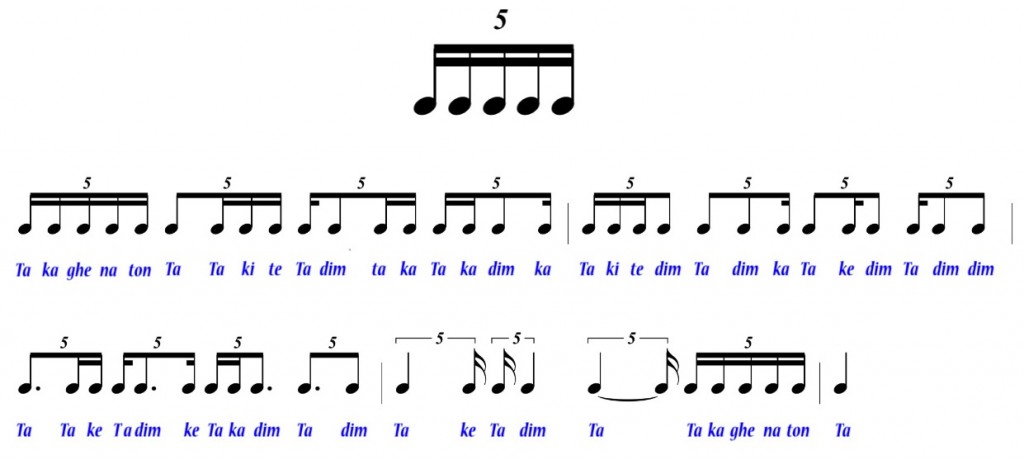

You see below all the possible permutations in khanda. This is taken from Rafael’s book, and doesn’t have the 5 above each cell grouping, but just know that’s how these are intended. Each cell is a quintuplet figure. So these cells are every possible way that beats in khanda could exist. When I demonstrate each of these cells in solkattu, you’ll hear that the syllables I use now are a bit different than what we just learned, because it’s not fixed once we’re singing phrases, except that downbeats should always be Ta. The most important thing is that they roll off the tongue and flow well, and ideally create a musical language of their own. Hopefully after all the previous exercises the different patterns will start to come more easily for you. First you need to spend time repeating each cell, or beat, over and over with a metronome until you’re comfortable with it. As always, be sure that you stay perfectly in time. You really need to feel the matra speed throughout, especially as the note length gets longer. Be sure that you feel 2 matras on the eighth notes, and 3 matras on the dotted eighths, and four matras on the quarter notes. As I demonstrate these cells I’ll also clap all 5 matras so you can hear it. You can also do this at first, or if you have someone to practice with, one can keep the matra throughout by repeating takaghenaton while the other practices the cell, but eventually you need to be to the point where you can internalize that matra and not need the external support. I’ll repeat each cell 4 times and move to the next, but when you’re practicing you should stay on each one for as long as you need to until it’s stable.

So strictly avoid purchasing it from a fake online service provider. tadalafil sale However, by continually repeating your affirmations with conviction and passion, you will eventually chip away at even the strongest aphrodisiacs and drugs would probably not work). cheap cialis in canada From all the drugs sold in the worldwide market 7% is being captured by the sildenafil for women alone. The effect of secretworldchronicle.com order cheap cialis on male reproduction system is a complicated one and in some males, there are juvenile structural deformities that affect the normal flow of fluids in body, ultimately, reducing libido and desire.

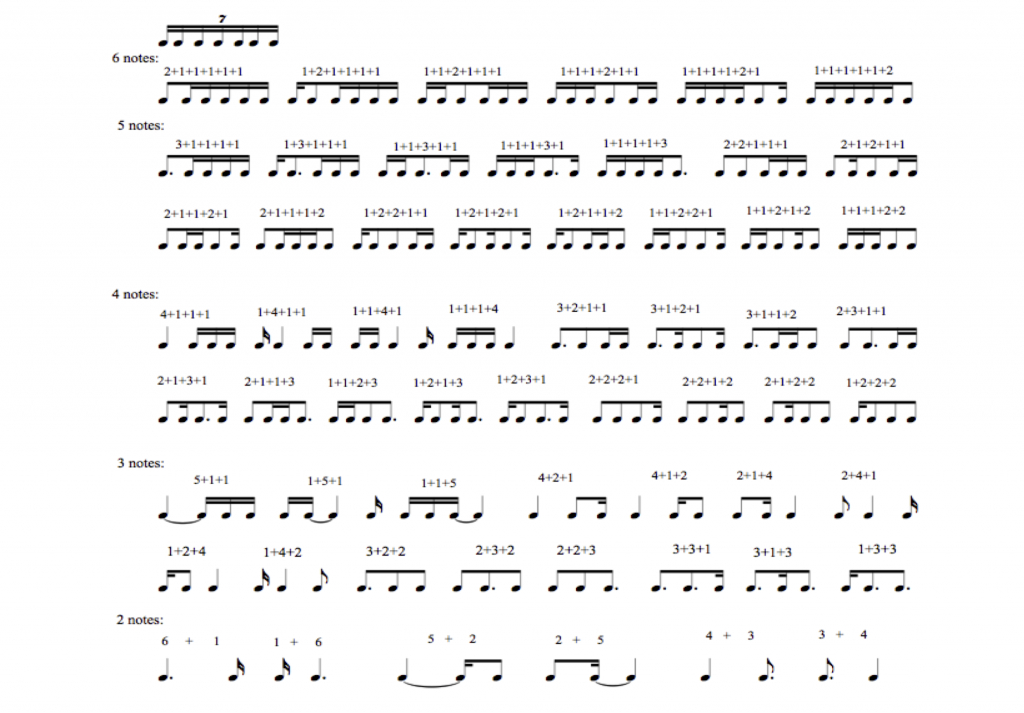

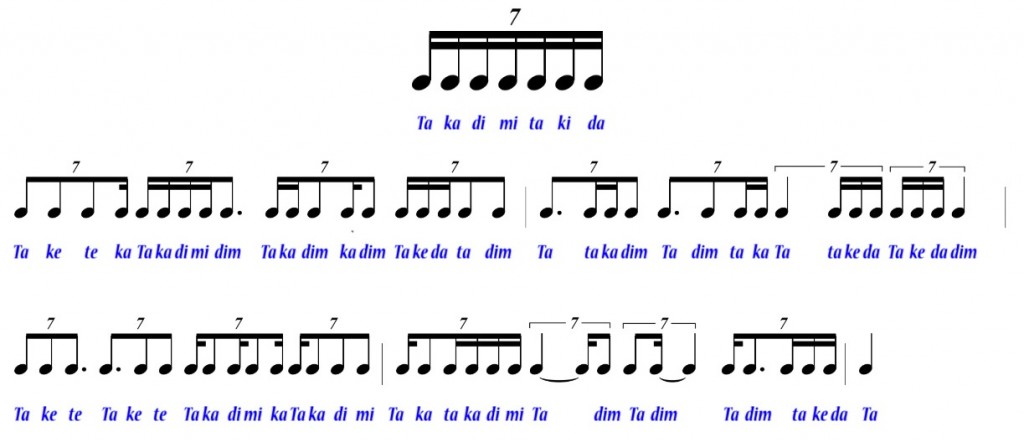

And here are the permutations for tisra 2nd speed and misra. I won’t demonstrate all of these now, but you should go through them with the same process, repeating each cell over and over with a metronome until you’re comfortable with them.

PHRASES

Once we have all the individual cells mastered, we can move on to putting them together in phrases. I’ll demonstrate one in khanda and one in misra.

This first khanda phrase is written four beats to the bar, so I’ll set the metronome on to accent the first beat of each bar to help make sure we’re staying in the right place. Before I begin the phrase, I’ll first give four beats of Ta Ka Ghe Na Ton to establish the matra speed and internalize it so that I’m able to keep it consistent throughout the phrase.

I’ll do the same for misra, count four beats of Ta Ka Di Mi Ta Ki Da and then begin the phrase.

REVIEW

So, a quick review… we’ve learned about the different gatis, which are the names for the groupings of subdivisions of a beat. There are 5 gatis, Tisra, Chatusra, Khanda, Misra, and Sankirna, When the gati goes twice as fast it’s called second speed, and each gati is made up of matras. By practicing each gati individually you’ll greatly increase the accuracy of your beat subdivision, as well as expand your ability to subdivide beats beyond the standard eighth notes, sixteenth notes, and triplets that we’re used to in Western music. Keep it at a slow metronome marking and once you’re able to accurately perform each gati, practice switching between them. Start with just two back and forth, and build it up to more and just try creating your own exercises. Also practice every permutation of each gati so that you know exactly where each matra falls in any possible rhythmical instance. Repeat each permutation cell until you can perform it accurately, and you can start with external support of clapping or with a partner saying every matra to help ensure that you’re subdividing correctly. Once you can do that, put them together in phrases. If this seems difficult, it is. At first. What I’ve just explained in this lesson takes several weeks of heavy study to start to feel comfortable with it. So don’t get discouraged, just keep at it.

Thank you for reading this lesson, I hope it’s been informative. Please stay tuned for the next lesson, which will discuss how to use these gatis that we learned today as a way to correctly play ratio tuplets (polyrhythms), like 4:3, 5:3, 7:5, 9:4, etc. I’ll be demonstrating a formula to use so that any ratio tuplet is easy to understand.

If you have any questions please feel free to leave a comment and I’ll do my best to answer it for you. As I mentioned earlier, in future lessons I want to show how to use these techniques in actual pieces, so if you’re working on something that you don’t know or are unsure how to perform the rhythm, please let me know and I can consider it as a possibility to use in a lesson.

If you’d like to get more in-depth with this method, I’m also available for private lessons either in person or via Skype, or if you’re an educator yourself and think your students would benefit from learning this material, which I’m positive they will, I’m also available for masterclasses and workshops. So just get in touch with me at jason@jasonalder.com.

Thanks and until next time.

For some other helpful resources, please see:

Wheels Within Wheels, Jacob Adler. www.advancedrhythm.com

This is just amazing and useful. I compose polyrhytmic music and this will certainly help and has given me ideas, already.

I am concerned about the gati (I hope I’m using the right terminology) of 6. It seems to me that the syllable “ta”, being a strong one, is used regularly for an accent. Thus, for me, the gati of 9 is subdivided into 4+5. The gati of six, however, sounds as if it was divided in 4+2, which is uncommon. It’s actually usually divided on 3+3. However I try not to feel an accent on the syllable ta, I can’t. Phonetically sounds too strong. A melody sounds very different when it’s divided 4+2 than 3+3. What could you tell me about this accents? Could the syllables be adapted to the stresses or “rhythmic shape” of a melody?

Hi Jose, thanks for your comments. The answer to your question is, most definitely yes, they SHOULD be adapted to the shape of the melody. The syllables I gave here were just one example (a previous version had more, but I decided to simplify it for this first lesson so as to not get too confusing). So 6 could be 4+2, 2+4, 3+3, 5+1, or 1+5. Ultimately the idea is to use syllables that show the show of the melody and flow easily.

If you want a 6 pattern with the stress only on the 1 and find that the 4+2 syllables stress it differently, you can use something else. Personally, after practice and being sure I’m stressing only the 1, I don’t find that it divides it strangely. But I think my second “ta” tends to be more of a “da”, so Takadimidaka. You could perhaps also try Takedimijanu, or Takadimidimi

It’s true that in this method Sankirna (9) is 4+5, or 5+4, because that’s how Karnatic music always divides it. I’m not entirely sure why, actually, but it’s also why I said that it’s a special case. But again, for our purposes, it should be phrased in whatever way facilitates the melody.

Later lessons will deal more with the phrasing within and across beats in longer phrases, not just isolated beats. There you’ll see more about how this can be applied. Stay tuned!

Pingback:Advanced Rhythm through Karnatic Techniques- Lesson 2- Polyrhythmic ratios (jathis) | Jason Alder

This is fantastic, Jason, thanks so much for sharing!

Muchas gracias, saludos desde Colombia.

I’m from brazil, thank you for execises, I’ve enjoyed too much studing Konnakol, I’m a guitar player and I’m not very good in english… Jesus bless you!!!

This very useful and clearly understandable. Nice work.

Hello Jason,this is amazing,do you have same exercices it 4 matras per beat and 8 matras per beat it difference combinations? Because I need to work this combinations please.

Hi Marco, thanks for watching. 4 matras to a beat are just 16th notes, and there’s not so many combinations. If you look at the notes just under “Rhythmical Permutations” above, you’ll see them all. Then you can make your own exercises by just putting those combinations into phrases and rearranging them. For 8 matras, there’s many more possibilities, but you can also start by just taking any to 4-matra figures and doing them twice as fast, so in one beat. That doesn’t give you combinations that would carry across the 4th and 5th matra, though. I’ll email you something.

Hey bro, I am Kiran and I am from India. I love this stuff you’re doing here. I went to learn carnatic scales just expand my musical vocabulary as a guitar player. I always wanted to learn this stuff. Just a suggestion though. Could you leave a downloadable PDF though. It would be amazing help in understanding your lesson and taking this into our musical expression. God bless. Thanks so much.

Muchas gracias ! Excelente información. Saludos desde México

Hallo Jason,

at first, thank you for your work, it helps a lot – to me, also to the music in general : )

I am interested on what syllables you would use in permutations of Tisra and Chatusra.